The power of max-flow

The max-flow problem may appear a bit contrived at first. (Image: Wikipedia)

It’s clearly useful in situations where an actual notion of flow exists, such as planning water supply throughout a city, but naively that seems to be all it’s useful for. Surprisingly, this is a tremendous understatement of the power of the max-flow approach as a general framework for algorithmic problems.

1: Rescue shelter

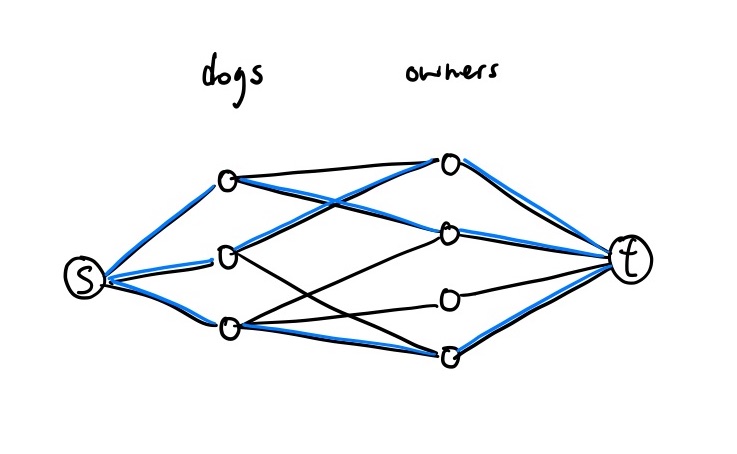

Suppose you work at a rescue shelter and are tasked with matching dogs with potential owners. Each dog has a set of owners that they can be matched with, and each owner has a maximum number of dogs that they can take care of. We want to make as many matches as possible. Oh, this is obviously a max-flow problem, right?

Yes, actually. Consider the dogs and owners as vertices in a flow network. Connect the dogs to the source with capacity \(1\) and the owners to the sink with their individual dog-owning capacities. Finally, connect the dogs to the owners according to their preferences, and the max flow in this network will be our desired optimal solution.

2: Toy blocks

Suppose you have some number of toy blocks and each block has letters on its faces. We want to know whether it’s possible to spell a given word using the blocks. This problem just calls “max-flow” to you, doesn’t it?

That’s because it is! It’s actually not that different from the previous problem. Consider the blocks and letters as vertices in a flow network. Connect the blocks to the source with capacity \(1\) and the letters to the sink with capacity equal to the number of times the letter appears in the desired word. Finally, connect each block to the letters it contains, and there is a solution if the max flow is the length of the desired word.

So what?

The great miracle is that the max-flow problem is very well-understood. In fact, there is the max-flow/min-cut theorem, which states that the maximum possible flow through a flow network is exactly equal to the capacity of the minimum cut, i.e. the cut dividing the network in two that minimizes the total capacity of the cut connections. This gives a bound on the max-flow problem in all cases (since all cuts are larger than the min cut), and in many cases it can give an exact solution.

In addition, we know a polynomial-time algorithm for solving the max-flow problem called the Edmonds-Karp algorithm. In fact, we know algorithms up to \(O(VE)\) and faster, although they are probably much more complicated.

3: Tunnel security

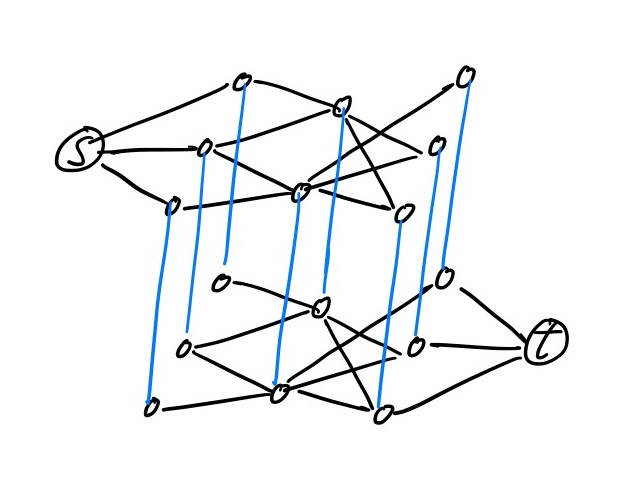

Now that we’ve introduced min-cut, it’s time to get funky. Suppose you’re tasked with protecting the entrance to a tunnel system, but your sensors aren’t perfect, so you need to make sure that every path into the tunnels hits at least two sensors. (Sensors can only be placed in the tunnels, not at intersections.)

At least this time we’re starting with something kind of like a flow network. The problem we want to solve is like the min-cut problem, except you need two cuts, whatever that means. No need to fret; we can just create an auxiliary flow network where the one-min-cut problem is equivalent to our desired two-min-cut problem! To do this, we duplicate the flow network into two “layers” and connect the vertices in the top layer to the corresponding ones in the bottom layer. And now we just need to solve the max-flow problem on this auxiliary flow network.

(We do need to ensure that our new connecting edges are not included in a min cut, but we can do this by giving them effectively infinite capacity.)

Further reading:

- Wikipedia page: see “Applications”