I became a mini-librarian and started reading again for the first time in years

At this point, I feel like books are kind of a bygone technology. It’s not that people don’t still read books. Of course they do. Probably thousands of books are written every year. But I do feel like they don’t occupy as essential of a role in Americans’ lives as they used to.

Before this semester, I hadn’t been reading a lot, and most of my friends didn’t read much either. Occasionally I’d have a book recommended to me, or I’d see one lying around and pick it up for a few minutes. Maybe this lack of appreciation for books was intensified by going to a technology school, where at least on paper, each discipline has a defined trajectory of technical skills you must learn in order to get where you want to be. This is why we take classes, I suppose – we learn theory and practice solving problems, which are both more reliant on structured instruction and less on storytelling.

But the glaring reason for people not reading nowadays (I probably deserve to get called a boomer for this) is that as a generation (Gen Z), our constant reliance on technology is providing other, more passive forms of learning / interest capture. Namely, I’ve recognized my own use of online video and social media to fill my desire to learn when I am too low-energy for books. It sucks though. I feel so drained after consuming media, since I rarely get the knowledge that I actually want, but at the same time it gives me just enough dopamine that I don’t want to go without it.

I know I just told you not to watch too many videos online, but I need some images for this blog post, so I might as well plug one of my favorite Spanish science channels, QuantumFracture. (Note to self, I should also make a list of YouTube channel recommendations at some point.)

Funnily enough, now that I’m writing this, I realize that I’ve actually been consuming book-like (longform) media for a while. I read Evan Chen’s Napkin in high school, and in my first year, I watched most of the 14.13 economics lectures on YouTube. I used to watch other lectures too, particularly math lectures I couldn’t really understand, like this talk by Jacob Lurie. (Reminder to write about category theory sometime.) But I still read a LOT more now than I used to.

In greatest contrast to the present, I had a phase last year where I would primarily learn by reading blog posts (see my other post). I found them to be more efficient, with broad intuitions condensed down into some kind of central maxim that I could apply right away, or a concise opinion piece that told me only the essential details I needed to understand the blogger’s viewpoint. If you’ve read my other post, I clearly take issue with this idea now. But it took me a bit to see the difference.

The story begins at my new living group, a cooperative non-fraternity with a rotating mealplan and decades of miscellany plastered all over its walls. And it has shelves and shelves of books, numbering into the thousands, that admittedly no one really reads. When I first moved in, I spent an afternoon reading on the living room couch, which was pleasant – maybe a little too pleasant. Predictably, as if in retribution, my semester quickly caught up to me, and I didn’t pick up another book for weeks. The book I had salvaged from the basement during work weekend sat on my desk, collecting dust, until I was miraculously elected house librarian, a small role that just involves reshelving books depositied in the book drop.

As I went around the house looking for the right shelves, my eyes skimmed the titles of countless books as I passed by, and I suddenly realized the sheer wealth and scope of information that was sitting on those shelves in front of me. Maybe I just hadn’t been exposed to the subject matters or styles of these particular books before (because for a long time I artificially restricted myself to the math and science sections at libraries, which honestly weren’t that great), but I found myself mentally shelving away more and more books in my internal to-read list: oral histories, poetry anthologies, books about ancient and modern societies. I guess this realization all happening at once might have been a byproduct of only recently having started to self-study the humanities and social sciences – I doubtless tried to learn about them in the same way I’m used to learning math and the natural sciences, which is from online lectures, textbooks, and problem sets, to no avail, before I tried books.

Yes, I have always appreciated the humanities. I write poetry, I love soulful music, and I spin fire. Having been close friends with a number of great people passionate about the liberal arts, I learned to appreciate deep investigations and revelations of being human. But I always saw them as a separate discipline from my personal worldly concerns, well, pretty much until I learned about anthropology. At that point, I had already been studying economics and sociology for a while, under the implicit assumption that the only practical, actionable statements that could be made about human society needed to be verified through experiment. Only through my mini-librarian role (and with the encouragement of an anthropology major friend) did I realize how powerful the field of anthropology is at dispelling misconceptions (a major shortcoming of empirics1) and getting at a deeper understanding of how people exist within their own societies. The humanities followed soon after: I realized that it is strictly impossible to understand societies without studying the humanities because of how they capture a broad swath of human experiences, which by their nature cannot be defined or summarized precisely (again, see my other post).

So I realized that reading books is a great way to learn about the humanities and social sciences. I suppose this isn’t that surprising really, but what was surprising to me is how much more context books are able to bring into a conversation due to their “storytelling” mode of information delivery. A book about the modern economy, even if it does revolve around modern economic theory, can bring significant depth to the conversation by including interviews with people playing different economic roles, or by discussing the controversial history of the relevant economic theory. All knowledge in this world is colored by our societal context, and I guess that is why I read.2

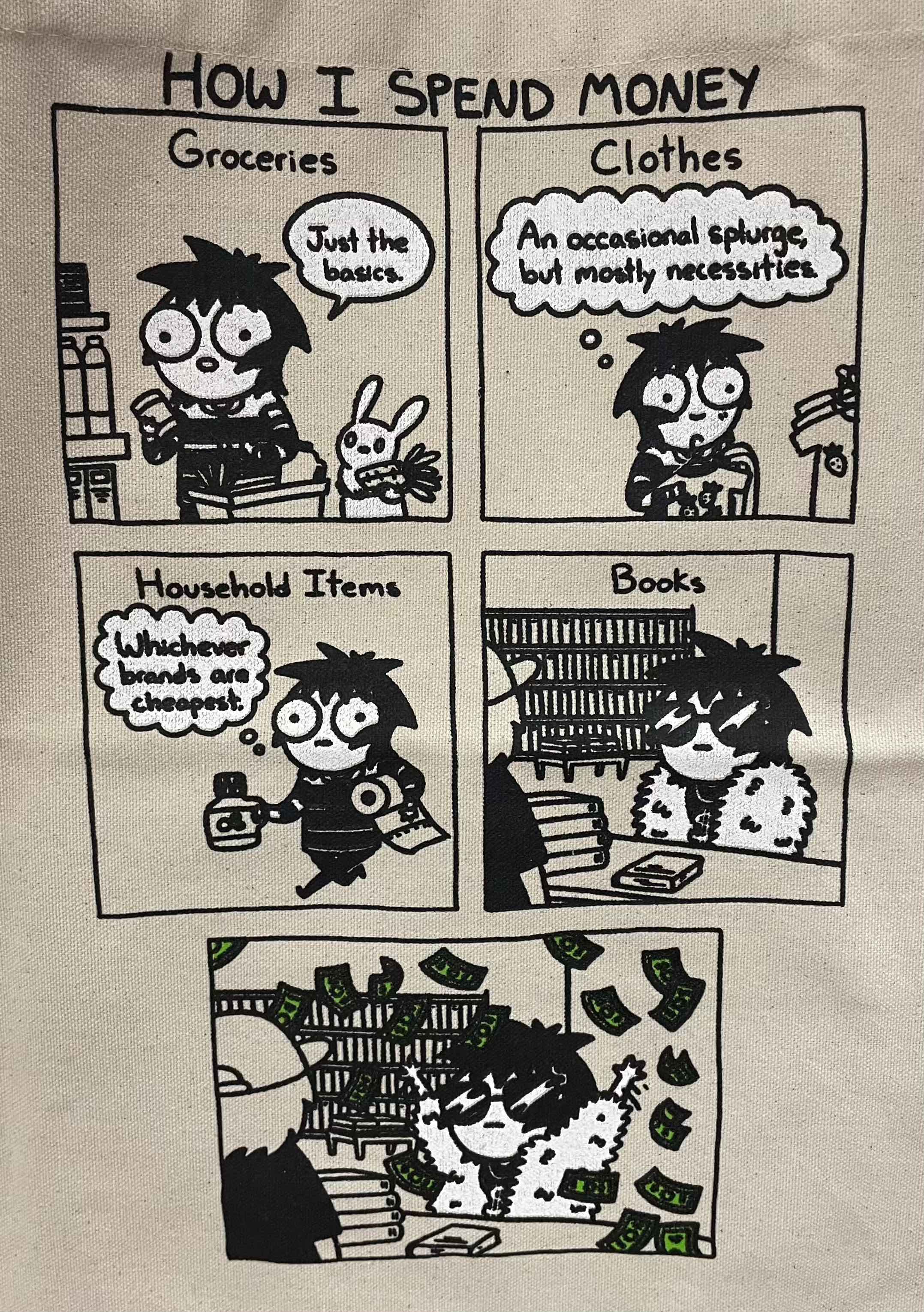

I found this Sarah Andersen comic on a tote and thought it was funny. Doesn’t represent me yet, but maybe in some of my possible futures?

Further reading:

- Economics Rules by Dani Rodrik is a book I recently had to read for class, but it presents a fine analysis of the shortcomings of models-based thinking. I think Rodrik is great, I would recommend reading his other stuff too.

- An insightful non-social-science book I’ve been reading is The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls, a memoir recounting the author’s experiences growing up with her eccentric, free-spirited, and at times dysfunctional family.

- I’ll make an actual page for book recommendations in a bit.

-

I know this is a strong statement, but hear me out. Empirical analysis inherently relies on some kind of underlying model for the data. People like to treat statistics as objective, but it’s only ever objective with respect to the model used for analysis. A great example is Simpson’s paradox, where you can reach opposite conclusions about the same data depending on how the data is grouped. This created real issues when UC Berkeley was accused of broadly discriminating against women in grad school admissions, but when the data was split by department, it revealed huge variation across departments, with some actually discriminating against men. Another classic example is that of confounding variables, or “correlation is not causation”: we know that going to school for more years helps with getting a higher-paying job, but how much exactly? When you consider the impact of parents’ education on both variables, the correlation decreases significantly (here is a very detailed article about the effect of education on income). Finding confounding variables is probably the most important part of any econometric analysis, and a lack of understanding of the core mechanisms of a casual effect (i.e. understanding what concretely goes on in people’s lives) is fatal. Yes, IV regression exists as a way to circumvent listing all confounding variables, but of course it still relies on significant assumptions (that the instrument has no effect on the outcome except through the endogenous variable). I will say that, yes, making progress towards “understanding people’s lives” through reading anthropology is really difficult to quantify. But that doesn’t mean it’s not worth trying – I do think a broad understanding will show its usefulness in thousands of small ways over time. ↩

-

Admittedly I read way more nonfiction than fiction, but I like to say that I haven’t found my fiction niche yet. The Three Body Problem and Kafka on the Shore were pretty good. ↩